The Truth About Nuclear Holocaust

A post-mortem on the Iranian nuclear "threat" and a study in propaganda tactics

Israel's war with Iran has ended with a tenuous ceasefire, despite this dénouement our media briefly stoked fears about 400kg of missing Iranian uranium. The public is led to believe Iran poses a nuclear threat with a narrative designed to overwhelm our amygdalas with trepidation at the prospect of a hostile Middle Eastern nation deploying nuclear weapons. This article will shrink your amygdala, assuaging those fears, but first we must dive headfirst into nuclear horror.

On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped the atomic bomb "Little Boy" on Hiroshima, Japan. The reports coming out of Hiroshima became the starting point of the non-proliferation movement and the inspiration for Hollywood movies that contribute to fomenting fear of nuclear weapons within the public consciousness. In order to assess the risk of nuclear weapons, we must first explore how these weapons work. Little Boy is a gun-type nuclear explosive, which can be produced in less advanced research facilities, making it an accessible weapon for technologically-advanced states.

Gun-Type Nuclear Explosives

A gun-type nuclear bomb operates on a relatively straightforward principle, leveraging the power of nuclear fission. The weapon’s core mechanism involves rapidly combining two subcritical masses of fissile material, typically uranium-235, into a single supercritical mass. This is achieved by firing one smaller mass, or "bullet," down a barrel-like tube into a larger "target" mass using a conventional explosive propellant. The collision triggers a runaway chain reaction, as densely packed neutrons split atomic nuclei, releasing immense energy in a catastrophic explosion.

Crafting a gun-type nuclear explosive can be achieved with rudimentary engineering, but for states wishing to acquire a nuclear weapon the obstacle lies in enriching uranium to obtain sufficient uranium-235. Naturally occurring uranium is mostly uranium-238, with only about 0.7% uranium-235, the isotope capable of sustaining a fission chain reaction. Enrichment involves separating these isotopes through complex, resource-intensive processes like gaseous diffusion or centrifugation. These processes remain a significant barrier for aspiring nuclear powers as they require advanced technology, significant energy, and precise engineering.

The Destruction of Hiroshima

A gun-type nuclear explosive unleashes catastrophic destruction. The aftermath of the bomb detonating over Hiroshima was grim. The civilian death toll is estimated at around 140,000, with tens of thousands killed instantly by the blast and firestorm, and many more succumbing to radiation sickness and injuries in the weeks and months that followed. Survivor accounts, as documented by John Hersey in his 1946 work Hiroshima, are harrowing. Hiroshima captures the human toll through the experiences of six ordinary citizens whose lives were shattered by the bomb.

Hiroshima brought the realities of the atomic bomb to a global audience, shattering the sanitized American propaganda narratives of wartime victory. It was originally published in The New Yorker, occupying an entire issue of the magazine. The work reached millions, later appearing in outlets like The New York Times and syndicated publications.

“MR. TANIMOTO, fearful for his family and church, at first ran toward them by the shortest route, along Koi Highway. He was the only person making his way into the city; he met hundreds and hundreds who were fleeing, and every one of them seemed to be hurt in some way. The eyebrows of some were burned off and skin hung from their faces and hands. Others, because of pain, held their arms up as if carrying something in both hands. Some were vomiting as they walked. Many were naked or in shreds of clothing. On some undressed bodies, the burns had made patterns—of undershirt straps and suspenders and, on the skin of some women (since white repelled the heat from the bomb and dark clothes absorbed it and conducted it to the skin), the shapes of flowers they had had on their kimonos. Many, although injured themselves, supported relatives who were worse off. Almost all had their heads bowed, looked straight ahead, were silent, and showed no expression whatever.”

-Kiyoshi Tanimoto’s account, John Hersey, Hiroshima, 1946.

Ordinary citizens, for the first time, were exposed to the horrors of melted flesh, vaporized bodies, and a city reduced to rubble. They learned of those exposed to the bomb’s flash experiencing excruciating burns, blackened peeling skin, tissue charred to the bone. Some had patterns of clothing burned into their flesh due to differential heat absorption. Their burns were prone to infection and slow to heal, exacerbated by the lack of medical resources and knowledge about the effects of radiation.

Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge, a German Jesuit priest, was on a mission in Hiroshima when the bomb struck. His accounts of tending to the injured and attempting to rescue people from the irradiated city are gruesome, depicting scenes of unimaginable suffering as he navigated a landscape of charred corpses and desperate survivors. Despite his own injuries and the onset of radiation sickness, Kleinsorge remained in Japan, devoting himself to the hibakusha (survivors) until his death in 1977. After years of battling chronic health issues, including fever, diarrhea, and organ dysfunction caused by long-term radiation exposure, he fell into a coma and passed away.

“On his way back with the water, he got lost on a detour around a fallen tree, and as he looked for his way through the woods, he heard a voice ask from the underbrush, “Have you anything to drink?” He saw a uniform. Thinking there was just one soldier, he approached with the water. When he had penetrated the bushes, he saw there were about twenty men, and they were all in exactly the same nightmarish state: their faces were wholly burned, their eyesockets were hollow, the fluid from their melted eyes had run down their cheeks. (They must have had their faces upturned when the bomb went off; perhaps they were anti-aircraft personnel.) Their mouths were mere swollen, pus-covered wounds, which they could not bear to stretch enough to admit the spout of the teapot. So Father Kleinsorge got a large piece of grass and drew out the stem so as to make a straw, and gave them all water to drink that way.”

-Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge’s account, John Hersey, Hiroshima, 1946.

Father Kleinsorge experienced acute radiation sickness, resulting from high doses of ionizing radiation. He experienced a cascade of symptoms: nausea, vomiting, hair loss, internal bleeding, and severe fatigue. Radiation damages bone marrow and blood cells resulting in a weakened immune system, which leads to infections, and for many — death. Long-term hibakusha like Father Kleinsorge faced chronic radiation effects, including cancers, cataracts, and organ failure. Leukemia rates spiked amongst survivors in the decades that followed.

John Hersey’s publication catalyzed two pivotal movements: the nuclear non-proliferation movement and the pervasive nuclear panic that defined the Cold War. By 1955, the first World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs convened in Hiroshima, though the movement would see little successful for decades to come. They sought to galvanize public opinion against nuclear technology, but governments seized on the opportunity to exploit the public fears that followed a Hersey’s attempt to bring forward painful truths.

The following video is not for the faint of heart, as it shows footage of radiation burns and wounded children.

Cold War Propaganda

Propaganda is typically thought of as the manipulation of media, but the United States utilized behavioural propaganda in the stoking of widespread public fear during the Cold War. Public schools implemented “duck and cover” nuclear drills as part of standard safety protocols, instructing children to hide under desks or against walls in the event of a nuclear attack. These drills were entirely performative as surviving the gamma radiation from a nuclear blast would require sheltering behind a concrete barrier at least 50 centimeters thick.

The drills were orchestrated by the American government to suit their agenda of amplifying public fear of the Soviet Union. The drills became a major feature of the Red Scare propaganda campaign. The visceral fear arising from the performances aided in the framing of the USSR as an existential nuclear threat. The U.S. cultivated a climate of paranoia, used to justify military escalation and domestic surveillance. The budding non-proliferation movement, which aimed to educate the public about the horrors of nuclear technology to rally support for a ban, inadvertently played into the hands of propagandists.

The Nuclear Arms Race

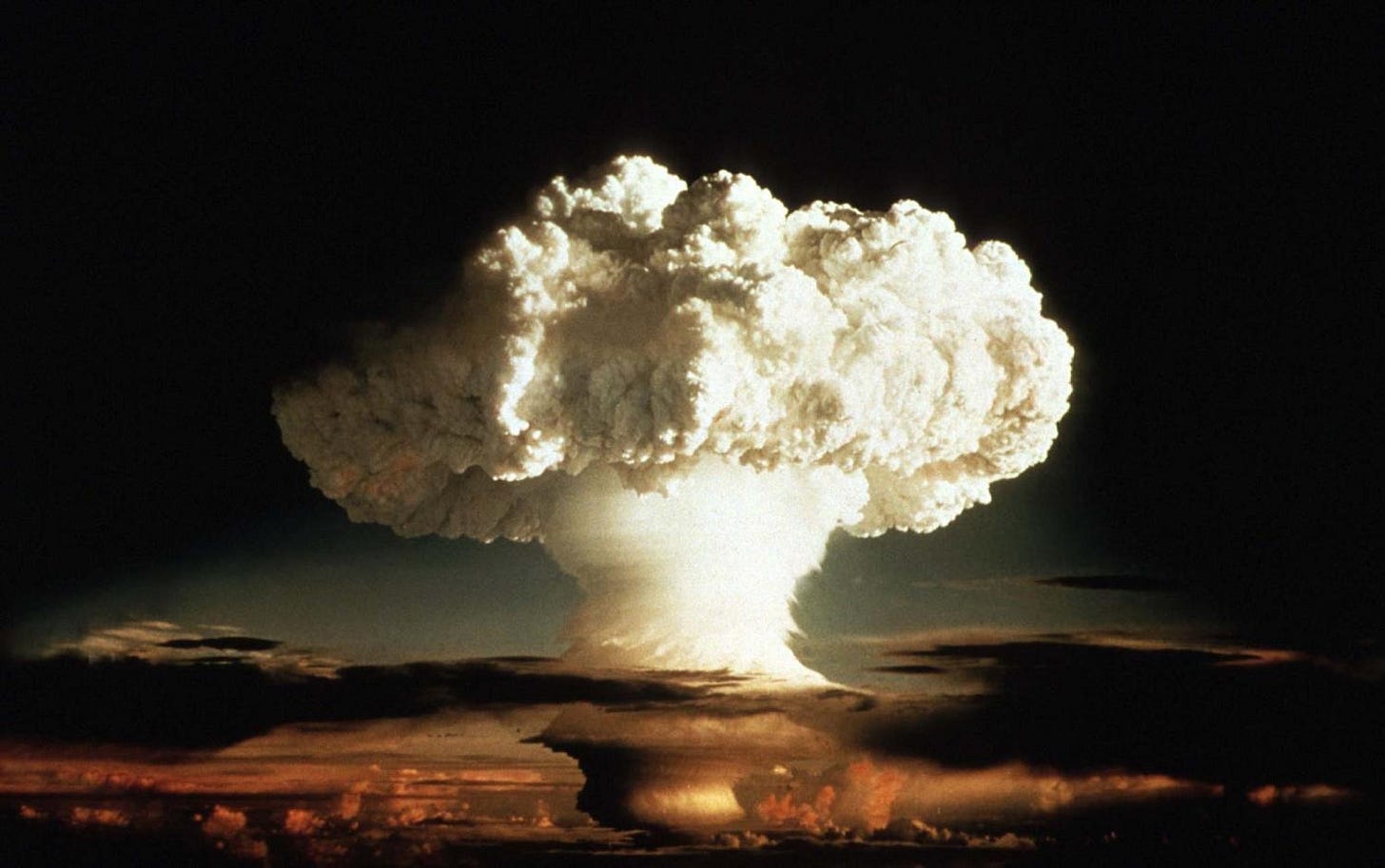

The 1945 atomic bombings of Japan triggered a frenzy of nuclear development among developed nations, with over 2,000 nuclear tests conducted worldwide during the 1960s alone. France, the United Kingdom, and Australia contributed to this count, but the Soviet Union and the United States were the predominant contributors, conducting 499 and 635 tests, respectively. New types of nuclear explosives emerged, including fusion-based devices and the hydrogen bomb, a fission-fusion-fission weapon capable of yields in the megaton range. The hydrogen bomb is orders of magnitude more destructive than Hiroshima’s Little Boy.

The Soviet Union tested the Tsar Bomba on October 30, 1961, the most powerful nuclear device ever detonated, unleashing the equivilient of 50 megatons of TNT over an uninhabited island in the Arctic Ocean. This thermonuclear bomb created a fireball visible 1,000 kilometers away and a shockwave that circled the Earth three times. The frenzied pace of nuclear testing reinvigorated the non-proliferation movement as global environmental concerns mounted over the widespread fallout from such tests. Residual radiation’s impact on local populations became undeniable, particularly after the U.S.’s controversial 1954 Castle Bravo test in the Marshall Islands, where a 15-megaton hydrogen bomb caused acute radiation sickness among nearby islanders.

No nuclear weapons have been used against human targets since the U.S. bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, a restraint largely attributed to the doctrine of mutually assured destruction (MAD). This principle, rooted in the certainty that a nuclear attack by one superpower would trigger a devastating retaliatory strike by the other, effectively deterred direct nuclear conflict between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. By the mid-1960s, both nations had achieved nuclear parity, rendering the use of such weapons, even in proxy wars, unthinkable due to the risk of escalation.

The Non-Proliferation Treaty and its Consequences

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) was formalized in 1970 with 191 states as signatories. The non-proliferation movement finally could claim success. The treaty is the most abided arms treaty in history and has been heralded as a cornerstone for global security. Yet, its promise of a safer, more stable world rings hollow. The treaty has left a trail of turmoil. Several regimes that relinquished their nuclear ambitions now grappling with instability and conflict.

Iraq’s nuclear ambitions, pursued in the 1970s and 1980s, were crippled by Israel’s 1981 Osirak strike and dismantled in the 1990s under UN inspections following the Gulf War, leaving Iraq without a nuclear deterrent. Saddam Hussein’s strategy of maintaining WMD ambiguity to deter regional rivals like Iran backfired, fueling Western suspicions of a reconstituted nuclear program, especially after Iraq expelled UN inspectors in 1998. Post-9/11, the U.S. Bush administration, driven by flawed intelligence, cited Iraq’s alleged WMDs, to justify the 2003 invasion, despite inspectors finding no active programs. After Saddam was ousted and a Western-backed democratic regime was installed, Iraq became a hotbed for terrorist groups, such as ISIS.

Libya, under Muammar Gaddafi, pursued a nuclear weapons program from the 1970s to the early 2000s, acquiring centrifuge technology from the Pakistani A.Q. Khan pro-proliferation network. Libya’s nuclear program was far from a functional bomb, but Western nations imposed sanctions which economically isolated the country. In 2003, Gaddafi voluntarily dismantled Libya’s nuclear programs, fearing his country would follow Iraq’s fate. However, despite normalizing relations with the West, Libya faced regime change via NATO intervention under UN Resolution 1973 to “protect civilians” following a harsh response to the Arab Spring uprisings. These uprisings were fomented by American NGOs such the International Republican Institute (IRI), National Democratic Institute (NDI), and Freedom House; and Wikileaks cables exposed U.S. government involvement in funding opposition groups. Gaddafi met a gruesome end, brutally sodomized with knife-points and dragged half-dead through the streets tied to a pickup truck, a destiny he might have escaped had he not abandoned his nuclear ambitions.

Ukraine’s surrendered its Soviet-inherited nuclear arsenal by 1996, under Western pressure. Ukraine was left defenseless, trapped in a destabilizing clash between Western colour revolutions and Russia’s predatory aggression. Taiwan, coerced by U.S. pressure to abandon its nuclear program in the 1980s, now faces China’s looming invasion threat, its non-nuclear status leaving it dependent on fickle American backing. Syria’s embryonic nuclear reactor, obliterated by Israel’s 2007 airstrike, gutted its strategic leverage, hastening the destabilization of Assad’s regime.

Disarming has repeatedly left regimes vulnerable for exploitation. Conversely, North Korea, through cunning deception, shielded its nuclear program by conducting covert reactor development, evading detection with underground facilities and disinformation until achieving nuclear status by 2006. North Korea secured its regime against external threats.

Iran’s Nuclear Capabilities

As of 2025, Iran possesses approximately 400 kg of uranium enriched to 60%. A gun-type nuclear bomb, like the "Little Boy" design, requires 50–64 kg of uranium-235. While the design is publicly available in college textbooks, replicating it demands advanced engineering, including precise metallurgy and sophisticated delivery systems, which Iran currently lacks. Developing these capabilities would require significant effort and resources.

Whether Iran would use a nuclear weapon is uncertain, as it likely prioritizes deterrence against regional rivals like Israel over first-use. However, any nuclear action would provoke devastating retaliation from nuclear-armed states with far superior arsenals. Iran's leadership, despite using nuclear rhetoric to bolster domestic support, is pragmatic enough to understand that such provocation could be catastrophic. A retaliatory hydrogen bomb strike, for instance, could render Tehran uninhabitable for a decade.

Unfounded Fears of Clandestine Bombs

For sophisticated non-state actors, such as terrorist organizations, engineering a crude nuclear bomb is within the remote realm of possibility. However, acquiring the roughly 40–50 kg of highly enriched uranium needed for such a weapon is simply not feasible. Uranium is heavily guarded and secured under stringent international safeguards. Stealing or diverting a supply of uranium and assembling a device without triggering advanced detection systems, including radiation sensors and global intelligence networks, is a logistical nightmare. This scenario better suited for a Hollywood screenplay than serious consideration.

Clandestine groups utilizing dirty bombs are considered a more plausible threat. Dirty bombs combine conventional explosives with radioactive material to produce a localized explosion with limited physical damage and low-level radioactive contamination, resulting in minimal long-term harm. Concerns about their potential use emerged after the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991 with fears about unsecured nuclear stockpiles falling into the wrong hands. The likelihood of a dirty bomb attack still remains low due to stringent controls on radioactive isotopes. No confirmed dirty bomb attacks have been recorded to date. Public anxiety about dirty bombs has been overblown, particularly through post-9/11 fearmongering and exaggerated media portrayals.

A cosmic irony underlies the Western approach to Iran. Destabilizing a nation like Iran increases the risk that enriched uranium could fall into the hands of clandestine groups. This raises a critical question: why pursue policies that undermine a country’s stability, only to exacerbate the very proliferation threats the global order seeks to prevent?

Mutually Assured Destruction

It’s clear that nuclear deterrent is a far more suitable option than wilfully neutering yourself and taking it on blind faith that foreign powers will not destabilize your nation. North Korea heard this message loud and clear, and has protected itself by acquiring nuclear weapons. Meanwhile, Israel, which loudly condemns Iran’s nuclear ambitions, has never signed the Non-Proliferation Treaty and rejects any oversight of its own nuclear arsenal, which arguably poses a greater regional risk than Iran’s heavily monitored program, exposing a hypocritical double standard in the global nonproliferation regime.

The specter of nuclear annihilation has haunted humanity since Hiroshima, yet nations wielding these weapons have acted with restraint, using them solely as deterrents. The Cold War doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) ensured stability between superpowers, but the non-proliferation movement obscured this reality, fostering a perception of inherent danger that destabilized the global order. Regimes like Iraq and Libya were pressured to abandon nuclear ambitions, leaving them without the deterrent shield nuclear capability provides. Responsible nuclear powers, including adversarial ones, have historically exercised restraint, as seen in the U.S.-Soviet stalemate or India-Pakistan’s cautious post-1998 dynamics.

The Goal of Nuclear Fearmongering

Carl Schmitt’s “friend-enemy distinction” is a foundational concept in his political philosophy, articulated in The Concept of the Political (1927). It posits that the essence of politics lies in the binary opposition between "friends" (those aligned with a political community’s values, interests, or identity) and "enemies" (those perceived as existential threats to that community). This distinction is not merely personal or moral but inherently public and collective, shaping group identity and justifying political action, including war. For Schmitt, the enemy is not necessarily evil but an "other" whose existence challenges the unity or survival of the political community. The distinction is dynamic, allowing elites to designate enemies based on strategic needs, often amplifying fear to consolidate power or mobilize support.

Schmitt’s framework illuminates how adversaries are constructed to serve interventionist goals. Propagandists leverage the friend-enemy distinction by framing Iran as an existential nuclear threat, positioning it as the "enemy" against a unified "friend" group, Western nations or allies like Israel. This binary is reinforced through narratives that emphasize Iran’s alleged pursuit of nuclear weapons, its defiance of international norms, and its ideological opposition to Western values. By amplifying these traits, propagandists transform Iran into a "nuclear bogeyman," a dehumanized other whose threat justifies preemptive military action or regime change.

Walter Lippmann’s concept of stereotypes, as outlined in his 1922 book Public Opinion, provide insight into how governments and media manipulate public perceptions. Lippmann said that stereotypes, “pictures in our heads”, are simplified, often distorted mental images that the public uses to navigate complex realities. These are not spontaneous but deliberately shaped by governments and media to streamline information and sway opinion. Governments exploit nuclear anxieties by crafting vivid, fear-laden stereotypes of nuclear technology as inherently catastrophic, drawing on historical traumas like Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Cold War imagery of fallout shelters, and Hollywood’s apocalyptic narratives such as Dr. Strangelove or The Day After. These images, embedded in public mind, prime populations to view nations like Iran as a “mad mullah” regime hell-bent on nuclear chaos, despite its IAEA-monitored program showing no evidence of weaponization.

The perpetual penality that traverses all points and supervises every instant in the disciplinary institutions compares, differentiates, hierarchizes, homogenizes, excludes. In short, it normalizes.

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish, 1995, p. 183.

Michel Foucault’s concepts of biopower and governmentality provide a framework for understanding how the U.S. disciplines allies like South Korea, Taiwan, and Saudi Arabia to enforce non-proliferation, perpetuating their dependence on American hegemony while manipulating nuclear fears to control populations. Biopower refers to the state’s power over life itself, managing populations through technologies of control that regulate behavior and shape collective anxieties, such as fears of nuclear annihilation. Governmentality, meanwhile, describes the art of governing through institutions, discourses, and practices that produce compliant subjects aligned with state interests.

In this context, the U.S. deploys biopower and governmentality to discipline allies, using economic sanctions, diplomatic pressure, and security guarantees to block their nuclear ambitions, ensuring strategic alignment while framing nuclear risks to justify control. For instance, South Korea’s nuclear program was halted in the 1970s under U.S. threats to withdraw economic aid and security support, reinforced by narratives of nuclear instability on the Korean Peninsula. Similarly, Taiwan’s nuclear efforts were curtailed by 1988 through U.S. intelligence leaks and diplomatic coercion, leaving it exposed to China’s growing power. Saudi Arabia’s 2024 push for uranium enrichment faced U.S. sanctions and warnings, tying its non-nuclear status to continued access to American military support amid its rivalry with Iran.

The antidote to this manipulation is knowledge. Nuclear weapons pose little realistic geopolitical threat when used responsibly as deterrents, as history since 1945 proves. Share this truth to combat fearmongering politicians and propagandists, lest we foster a world of naïve pacifism where nations, robbed of nuclear sovereignty, are destabilized by those who wield fear for the sake of power.